Public-key cryptography

In symmetric encryption the same key is used both for encryption and decryption. In public key cryptography we have a separate key for encryption and another one for decryption. This makes sense if it is hard to determine the decryption key even if the encryption key is known.

If this is the case then you could tell everybody how to encrypt messages they want to send to you but still only you would know how to decrypt these messages. This explains the name: encryption key could be made public while the corresponding decryption key still remains secret.

Typically the keys are longer and the algorithms are slower in public-key cryptography than in the symmetric encryption. But with public-key cryptography you are able to do things which cannot be done with symmetric encryption.

The above mentioned possibility for even strangers to send confidential messages to you is one such thing. Digital signature is another such thing: Using public-key cryptography it is possible to sign messages electronically and to authenticate users and their messages.

Let us denote by the remainder when is divided by . The here is called the modulus. For example, and .

Also, we make use of prime numbers, shortly primes. An integer, larger than 1, is a prime if it is only divisible by 1 and itself. For example, 7, 101 and 7823 are primes but 6, 15 and 100 are not.

Given integers , and , it is easy (at least in principle) to calculate . This modular exponentiation is relatively easy to do even when the integers , and are very big. With big and the power becomes huge. Luckily we do not have to compute this huge number at all. Instead, it is possible to compute the remainder for each intermediate value before continuing. Let us take a simple example: , , . Now .

We first compute . Then we take the remainder of this intermediate result: . Next we raise 21 to the power of 3. The result is 9261. Taking the remainder again with the modulus 1003 we get 234. The final step is to raise 234 to the power of 2: the result is 54756. Taking the remainder again we get the final result: .

On the other hand, when arbitrary integers , and are given, it is very hard to find an integer such that . This problem is called the discrete logarithm problem. We use the notation

Because modular exponentiation can be done relatively fast even for large numbers but the inverse problem of finding the discrete logarithm becomes very hard for large numbers, modular exponentiation with large numbers is an example of a one-way function.

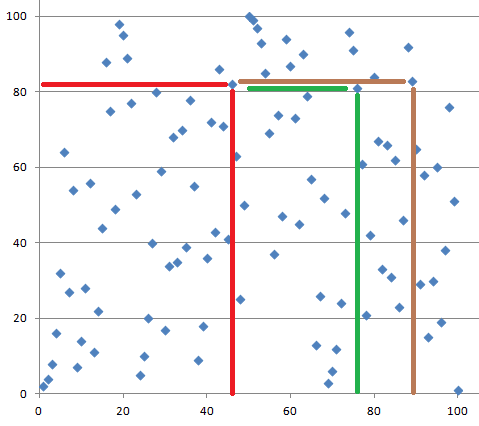

Let us take a closer look at the discrete logarithm with small numbers. We choose and below see a graph depicting .

Note that the graph is not smooth and it is not growing like the ’normal’ exponential function defined for real numbers. Instead, the graph seems to make random-looking moves.

A key agreement protocol is a method for two parties, say Alice and Bob, to agree on a shared secret key over an insecure channel, but still in such way that nobody else who is eavesdropping on the channel is able to learn the shared secret. An example of such method is Diffie-Hellman key agreement protocol.

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange begins by Alice and Bob agreeing on a modulus and a number . Then Alice picks a random number and sends Bob the number . Similarly, Bob picks a random number and sends Alice the number . Now Alice can calculate and Bob can calculate . These two values are both equal to and that value can now be used as the new shared secret key.

Our HTTPS example (TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384_256 bit keys,TLS 1.2) makes use of a certain variant of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

RSA

Next we take a look at how public-key cryptosystems look like. The most used system is called RSA. It is based on the following mathematical fact:

If and are primes, and and are such that

then for all values of it holds that , where .

To set up RSA keys, Alice first needs to find two large primes and . Both primes should be at least 1000 bits long. She then needs to pick an integer such that it is possible to find another integer for which

holds. The public key of Alice is now the pair , where . The private key that Alice needs to decrypt messages is the pair . Alice should not reveal the primes and to anybody.

Let us assume that Alice has given her public key to Bob. Bob can now encrypt any "message" that is (encoded as) an integer between 0 and by calculating .Bob would send the result to Alice. Alice can decrypt the cryptotext because she knows the secret decrypting exponent . She calculates .

A traditional signature is some ink on a paper. It is based on the assumption that only one person can write a signature in a certain way. A digital signature is always different for every message (otherwise you could just copy-paste it to any document) and only a person who has the signing key can calculate it correctly. The signature can be verified by anybody who has the verification key.

RSA can be used also for digital signing and verification. Alice reveals the verification key and uses herself the signing key . If Alice wants to sign message , she calculates the signature as . When Bob receives the message and the signature , he can check that . If this is true then the signature must be from Alice because nobody else knows the parameter thats is necessarily needed to calculate Alice’s signatures.

Usually the signature is not computed for the entire message but, instead, a hash of the message is computed first, and then the hash value is signed. This guarantees that the value to be signed does not become too big. On the verification side, similarly, the received message is first given as an input to the hash function, and parallel to that, the verification key is applied to the signature. If outputs from each operation are equal then the signature is accepted. The hash value of the message is called its fingerprint, and it can be used instead of the entire message if no collisions have been found for the hash function.

Our HTTPS example (TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384_256 bit keys,TLS 1.2) makes use of RSA for digital signatures.

Remember to check your points from the ball on the bottom-right corner of the material!